The Cardinal Virtues: Prudence, part I“The good must be loved and made reality”

Chivalry Guild

Chivalry GuildJan 15, 2023

https://thechivalryguild.substack.com/p/the-cardinal-virtues-prudence-part

I noted

last week that the language of the virtue has become horrible confused—and serious consequences have followed. Moral striving seems pointless when the words become diluted with connotations of lameness. In this essay I want to turn to the first of the cardinal virtues and look a little closer.

We’ve been led to believe the virtue of prudence is basically the art of small-souled calculation. The modern understanding takes the prudent man to be a clever tactician. He’s more evasive than good (and perhaps not totally trustworthy). We talk about prudence as though it were something like the coward’s virtue, which teaches a man to dodge those confrontations which might require him to be brave. According to this understanding, lying also is sometimes thought to be prudent (read: cunning, crafty).

Which should prompt a spirited person to ask: why would I want to be lame, calculating, cowardly, and dishonest? If that’s all this supposed virtue is, then to hell with it!

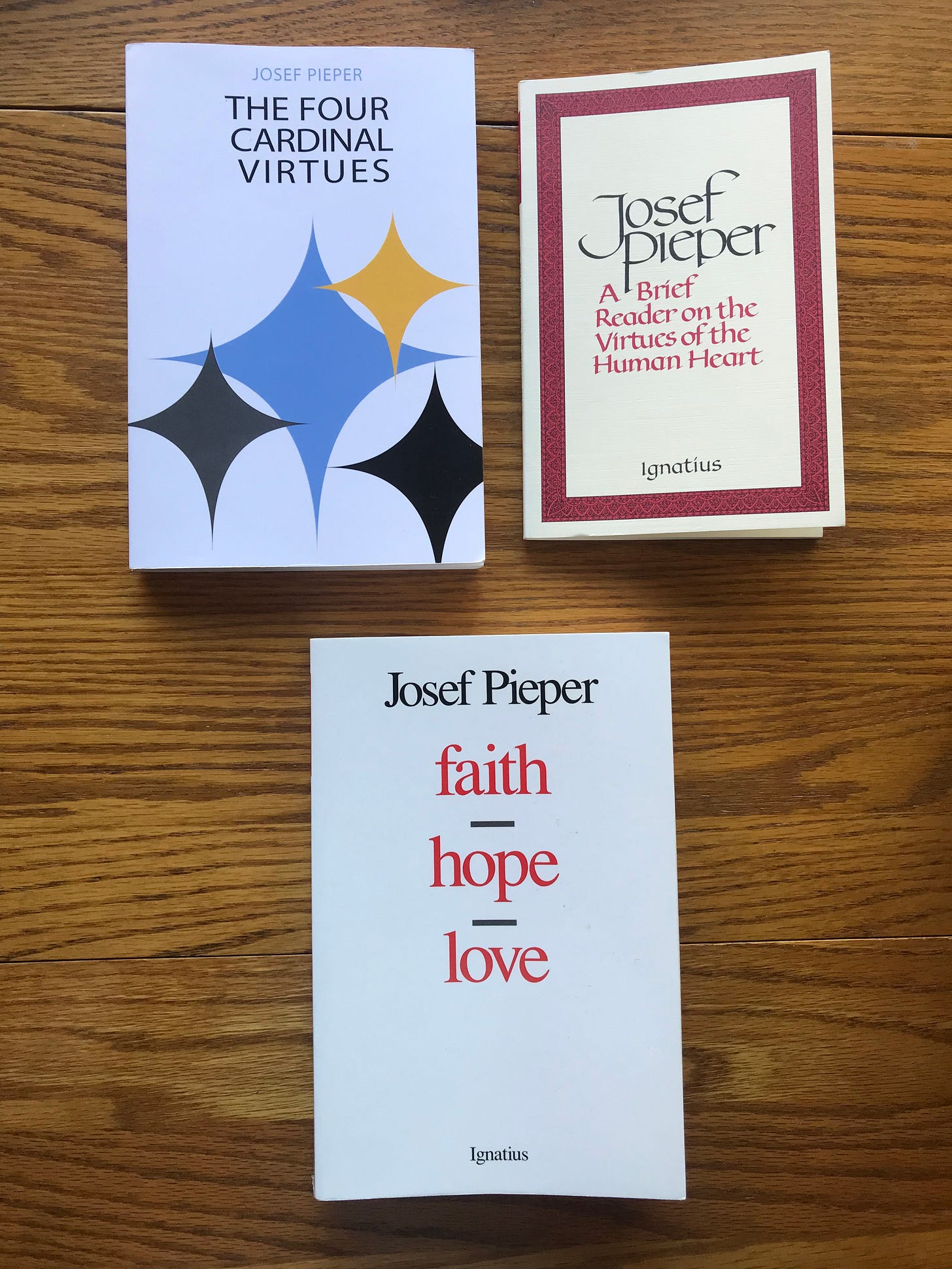

This was certainly how I understood prudence prior to reading Josef Pieper’s

The Four Cardinal Virtues, which reintroduces the teachings of Thomas Aquinas and the Western tradition before it was broken by the Reformers. Just a few pages in, my misconceptions were throttled. What I love about Pieper is his understanding of the futility of grumpy moralizing about how people need to act right, Jeremiads using language that no long has much hold on us. He understands the need to recover an older, truer, nobler, and more vigorous vision of the good life, and he suggests starting with the words themselves.

So, if prudence does not mean utilitarian calculation and quasi-cowardliness, what does it mean? Really the essence of the virtue is this: prudence is the art of making good decisions. Prudence turns knowledge of reality into accomplishment of the good.

Though a thoughtful virtue, prudence is not the domain of nerds and academics and their abstract theories; prudence is for the purpose of action. Prudence is for living.

The First of the Virtues

One of the most important things to understand about the cardinal virtues is that prudence precedes the others: justice, courage, and temperance. Acts are only virtuous when prudence declares them so—because, in order to make good things happen, we must have some knowledge of the good and how it might be made reality in the specific situations in which we find ourselves. Prudence performs this service as the “cause, root, mother, measure, precept, guide, and prototype of all ethical virtues; it acts in all of them, perfecting them to their true nature; all participate in it, and by virtue of this participation they are virtues.”

“All virtue is necessarily prudent,” Pieper explains, because “realization of the good presupposes knowledge of reality.”

Without prudence, any seemingly virtuous act is more like a lucky shot or an instinctive guess. We might, Pieper says, intuit the need for moderation in the consumption of wine, but these intuitions are perfected and made into something more only under the guidance of prudence.

This means, among other things, that good intentions are insufficient to justify a man’s course of action. When some unwise course of action blows up in our face, we cannot plead that we meant well, as though this lets us off the hook. We have a responsibility to know how to make our good intentions realized.

Against Instructional Manuals

Many implications follow from the primacy of prudence. One is that we cannot outsource our decisions to the experts, cannot turn to authorities for instructions on how to act in every circuмstance. Virtue thus opposes casuistry, the “branch of ethics which has as its aim the construction, analysis, and evaluation of individual cases.” The casuists would simplify our lives by publishing the requirements of conduct in manuals. In this case, do X. In that case, do Y. But prudence cannot be muscled out of the picture without great damage being wrought.

Smallness of soul is the result of trying to relieve men of their obligation of deciding well. Casuistry results in a “degenerate, anti-natural state of nonhuman rigidity,” turning ethical considerations into a “science of sins.”

(Teenagers asking “How far can you go?” are the perfect examples.

Is first base fine? Is second base a sin? Is it a mortal or venial sin? At what exact point on the basepath does one cross the line? Anyone wanting to publish exact instructions on these matters misses the point, in addition to provoking a good deal of deserved resentment.)

Prudence says that man cannot be reduced to a mere rule-follower. The point is to face the opportunities and challenges before you like a free man, rather than turning to some guru to tell you what to do. Your eyes must be clear and your judgment sound.

There are certain general requirements that apply always and everywhere: a man is always called to be just, courageous, and temperate. But the precise shape and form of virtuous actions might differ according to the time and place and the thousand different variables that accompany any particular situation. For example: a confrontation with a dangerous man might be necessary or it might be foolishly rash, depending on the risks, rewards, and reasons involved with the individual case. Only the prudent man will know the difference.

And in case it isn’t yet clear, the prudent man is more than willing to face tremendous risks when required. He knows to pick his battles, but he also understands that ultimately one must fight. Backing down from the right battle is failure to be prudent, a failure to understand how to bring about the good.

Conclusion

I hope to have done justice to this virtue, showing it to be about far more than small-souled calculation.

There’s a great deal more to say about prudence and how one might become prudent. I aim to write more soon. But for now we might take a moment to appreciate how wildly this differs vision from the commonplace claim that the Catholic one seeks to “control you.” As Pieper writes, “The doctrine of the preeminence of prudence lays the ground for the manly and noble attitude of restraint, freedom, and affirmation which marks the moral theology of the universal teacher of the Church.” Thomas Aquinas, writing on behalf of our tradition, asserts that we need this virtue if we are to live free and good lives.

Prudence: The Fighter’s VirtueWhen a UFC fights teaches about cardinal virtues

Chivalry Guild

Chivalry GuildMar 26, 2024

https://thechivalryguild.substack.com/p/prudence-the-fighters-virtueOne of my go-to themes is the

diminishment in our times of almost all the virtues. Modern life does not simply create conditions which militate against their development, but also makes the words themselves sound lame—less impressive, less invigorating, more inclusive, more Hallmarky. The new sub-virtues cease to be worth striving for. Why strive for something like meekness, chastity, or humility (as we understand them today) when these virtues are mostly pretty dorky?

It’s time to get serious about restoring their good name.

As for prudence, the first cardinal virtue, the word often conjures associations with small-souled cunning and calculation. In some usage, prudence and courage are antonyms. Prudence is thought to be the coward’s virtue, demonstrated whenever a man cleverly avoids those times when he might have to summon courage and risk himself. Better to be a fox than a lion, he tells himself, and skirt these tests altogether.

Real prudence could be thought of as the fighter’s virtue, and real prudence demands that certain risks be run. On the most basic level it is "the perfected ability to make right decisions,” in the words of Josef Pieper. Every decision must be made within a context, and contexts can differ wildly. So prudence is needed to determine what is required by the circuмstances before us; it is the virtue which identifies how to bring about the good from various challenges and opportunities, and directs us toward winning whatever fight we’re in. Victory rarely retraces the exact same path.

In

The Meditations, Marcus Aurelius says the art of life is more like boxing or wrestling than dancing. He means that the martial artist does not get to shuffle like a ballerina in whatever direction he chooses, but instead must stand ready to meet concrete difficulties in the form of opposition—someone looking to bash his face in. He will need to summon the judgment and strategy to meet and overcome his opponent. Life is a metaphorical fight.

Courage too will be needed for these fights. Far from being the coward’s virtue, prudence is that which gives meaning and shape to real courage. Josef Pieper writes that "All virtue is necessarily prudent” because prudence is the “measure” of the other virtues—and this includes courage. All courage is prudent. When the challenges before you require a risk—when that risk is worth it—the failure to rise to the occasion is not just cowardice, but also imprudence. You failed to understand what the moment demanded, and you likely lost the fight as a result.

UFC 299

A remarkable case study of the link between prudence and courage was on display in the main event of UFC 299, when Marlon “Chito” Vera found himself outmatched by a superior opponent in Sean O’Malley. It became

apparent early in the fight that O’Malley’s reach and boxing skills would allow him to piece Vera up, mostly avoiding danger himself while punishing his opponent.

Vera’s face told the story of O’Malley’s advantages.

If Vera was going to have a chance, he had to turn the fight into a brawl. He had to get inside of O’Malley reach, where he might hurt O’Malley in a wild scuffle. But that required running a huge risk and making himself vulnerable in the attempt, possibly getting knocked out. Courage of course was needed to run that risk. And before courage, prudence was needed to determine that the risk was worth running—that the risk was Vera’s only hope.

It would be ridiculous to say a highly-ranked tough guy like Chito Vera lacks courage in a more general sense. But during the fight—undoubtedly one of the biggest moments of his life—he showed continued hesitance to press the issue. And it didn’t just mean he would lose the fight. His hesitance meant that O’Malley would inflict more punishment; every minute that Vera hesitated was another minute of a beating, getting his face turned to sausage.

Then in the final seconds of the fight something wild happened. Vera finally made it a brawl. He got inside and hit O’Malley with a big shot to the body, just before the bell sounded. O’Malley appeared hurt enough that he had to sit down and gather himself immediately after the fight. If there had been just twenty more seconds, maybe not even that much, Vera would have been able to follow up his attack. Something crazy could have happened. He might be champion of the world today.

But it was too late.

Again, my point is not to delight in armchair critiques of accomplished fighters like Chito Vera. But his situation is such a good metaphor for life that it needs to be emphasized. The failure to put ourselves on the line can guarantee defeat. It can also prolong our pain. We cannot hide behind a false understanding of prudence and cannot dress up our fearfulness in fancy clothes while calling it virtue. When good judgment tells us that it’s time to take a risk, we need to listen. The fight and the cause depend on it—and maybe our lives too. Prudence is a fighter’s friend.