GREGORY DIPIPPO

The first part of this article summed up several of the observations offered by Frs Annibale Bugnini and Carlo Braga in their commentary on the 1955 Holy Week reform, published the following year in Ephemerides Liturgicae, of which Bugnini was then the director. The conclusion of their treatment of the blessing of the palms and the procession makes it very difficult to believe that this commentary is the work of honest men.

They tell us that a high degree of importance was given to the blessing, rather than to the procession, firstly because of the “internal elements of the rite which were then held in the greatest honor, such as the immoderate use of symbolism, and the oft-repeated mention of taking the blessed branches home, and putting them in the fields, to obtain protection in adversities by the force of the blessing given to the branches. In these things, the relationship (of the blessing) to the true character of the rite is completely ignored, that is, to render solemn honor to Christ the King through the procession.”

[color][size][font][font]

Thus, the “true” character of the rite was lost for a millennium amid the excessive multiplication of blessings, even though the blessings in the Missal of St Pius V are far fewer and shorter than those in its ancestor text in the Pontificale Romano-Germanicuм, and, as the authors themselves have previously stated, we have no clear evidence of any earlier form of blessing used at Rome. In other words, the “true” character of the rite is not to be found in any

actual form of it, whether then in use or used in the past, but only in the creations of the modern reformers.

They continue: “Nor should we discount the progressive decrease in the outward solemnity of the procession, from the magnificence of the rites of the 11th and 12th century, to the rite which is found in the Roman Missal (

i.e., of St Pius V), which is truly a pale memory of the glory of the preceding age.” Having just learned that the original creators of the rite composed the blessing in a manner that obscured its “true” character, we are now told that their work in arranging the procession was glorious, and we are the poorer for doing less than they.

Nonetheless, there is a very real sense in which this latter observation is perfectly legitimate, and the authors were not the first or the last to make it. For example, in “The Bugnini Liturgy and the Reform of the Reform” (pp. 26-27;

Musicae Sacrae Meletemata, vol. 5, 2003), the late László Dobszay made a similar point, that the Tridentine version of Palm Sunday lays rather more emphasis on the blessing than on the procession; and furthermore, that its version of the procession involves far less ceremony than those of other medieval Uses.

In a previous article of this series, I gave an outline of the considerably more complex procession done at Sarum; much the same holds for the rite given in the Pontificale Romano-Germanicuм, and in medieval Uses of the Roman Rite generally.

[/font][/font][/size][/color]

|

| A statue of Christ riding a donkey, a common feature of Palm Sunday processions in the Middle Ages. There were originally wheels in the four rectangular holes in the board; the hole at the front is for the rope with which it was pulled. (Southern Germany, ca. 1480, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.) |

[color][size][font][font]

Dobszay raises this point in order to argue that the ceremonies of the medieval Palm Sunday processions should be reintroduced. Bugnini and Braga, however, raise it

only so they can to paint their usual dreary picture of the state of the liturgy in the post-Tridentine Church. “… little by little, the people were excluded from active participation; for when the procession ended at the church door, they remained in their place in the church as inert spectators. … the Gospel reading, the purpose of which was to give the genuine sense of the celebration, was overwhelmed by so many extraneous elements, and lost its power to guide the (liturgical) action. The procession, having been taken away from the life of the people, became an element that says nothing to them; and therefore, the people had to find (‘invenire’, also ‘invent’) other things that spoke to them. … they found nothing that had any relation to their life other than the blessed branch …”

Note here the claim that it was the Gospel reading, and, as far as we can tell from what they have written,

no otherpart of the rite, which gave “the genuine sense of the celebration.” This claim is made despite the fact that as far back as we have records, the Gospel in this rite was always one among many diverse elements. It brings with it a charge of negligence against the Church, that it allowed that one all-important thing to be “overwhelmed by extraneous elements”, elements which just happen to be arranged in a manner very similar to that of the Catholic Mass. Martin Luther himself could not have put it better.

[/font][/font][/size][/color]

|

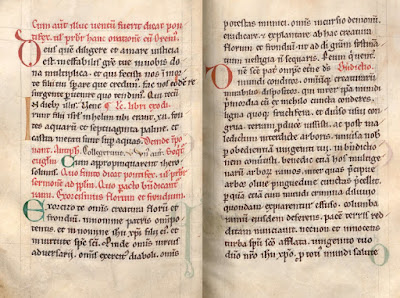

The beginning of the blessing of the Palms in a Pontificale made for the diocese of Płock, Poland, in the last quarter of the 12th century. The prayer “Deus quem diligere” is followed by the incipits of the Epistle, the gradual Collegerunt (labelled as an ‘antiphon’), and the Gospel, then an “exorcism of flowers and branches”, an element which is not included in the Tridentine Missal, and on the right-hand page, the first of five prayers of the blessing. This one prayer is by word-count almost as long as the first, second, third, and fifth prayers for the same blessing in the Missal of St Pius V put together. (Sem. Plock. 29 Mspł.; olim: München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 28938) |

[color][size][font][font]

As an historical explanation for the evolution of the rite into its Tridentine form, with its greater emphasis on the blessing than on the procession, this is nonsense. As they stand in the Missal of St Pius V,

both parts of the rite are the result of an abbreviation, not of a lengthening, and this was done not by the people, but by the clergy of the Papal court, who did not create their missal for use in parishes. However, this is not primarily what raises the suspicion of dishonesty. That suspicion arises, rather, from this: the authors do not mention here that the one ritual in the procession which

did survive into the Missal of St Pius V, the knocking on the church door with the processional cross, was suppressed in 1955. [22] This, despite the fact that they also present evidence that the knocking on the door goes back to the rite’s most ancient origins in Jerusalem.

One last major point remains to be noted.

The section of the commentary on the reform of Palm Sunday is twenty pages long; of these, the final eight are devoted to the singing of the Passion. An explanation for its division into three parts is given, one which is sadly typical of the reductive mentality of that period; namely, that it was done “so that its length would not burden the listeners”, even though many other rites have much longer readings of the Passion in Holy Week, all of which are sung by a single voice. [23] Much is made of the particular rites associated with it, such as the absence of “Gloria tibi, Domine” after the title. Nearly two pages of text and a full-page table are devoted to what is paraded as one of the reform’s great conquests, the abolition of the celebrant’s “doubling” of the readings.

[/font][/font][/size][/color]

[color][size][font][font]

In the midst of this, a single sentence, 31 words in the original Latin, is dedicated to the only change to the text of the Palm Sunday Mass. “From these (

i.e. from the Passions of Matthew, Mark and Luke, mentioned in the previous sentence) are removed the narration of the supper in the house of Simon, and the Lord’s Last Supper with the Apostles, so that (

the reading) has only the narration of the Passion properly so-called, from the entrance into the garden of Gethsemane to the Lord’s burial.” Nothing else whatsoever is said about the matter, but a helpful table is provided which lists and counts the verses removed.

This abbreviation of the Synoptic Passions removes the Gospel account of the Institution of the Eucharist not just from Holy Week, but from the liturgy, since these passages are read nowhere else in the year. This is not, of course, the only or

the worst way in which the 1955 Holy Week reform divorces the Mass from the Passion, and the Last Supper from the Cross; it is a general theme of the reform, which was in many ways

undone in the Novus Ordo.

The commentary does note elsewhere that the reading of the Last Supper together with the Passion on Palm Sunday is a uniquely Roman custom. I wonder whether its failure to say anything else about its abbreviation arose from some embarrassment on the authors’ part at this hideous mistake, since they were later so closely involved with the project which undid it.

Notes (continuing the numeration from the previous articles): [22] In point of fact, both new versions of the procession, those of 1955 and 1969, involve no particular ceremony whatsoever. Dobszay contends that the post-Conciliar reform fails in this regard because it takes as its starting point the already much-reduced Tridentine form, and reduces it further, where he would argue for a rediscovery of the richness of the medieval forms of the ceremony.

[23] In the Ambrosian liturgy, the Passions of Ss Mark, Luke and John are all read at a single ceremony, the Matins of Good Friday. On Good Friday in the Byzantine Rite, twelve Gospels are read at Orthros, the first of which is John 13, 31 – 18, 1; Passion Gospels are also read at the four Royal Hours and Vespers, and at Vespers of Holy Thursday, which is joined to the Divine Liturgy of St Basil. In the Mozarabic Rite, the Passion Gospels of the Holy Thursday and Good Friday are centonized from all four Evangelists. Both of these readings are longer than the Passion of St John; taken together, they are longer than the Passion of St Matthew, the longest of the four, by more than half.[/font][/font][/size][/color]